Greg Falk und Neil Carver von Carver Skateboards kann man als „Gründerväter“ des Surfskate bezeichnen.

Die Geschichte von Carver startete 1995 in Venice, Kalifornien. Den ganzen Winter 1995 hatten die beiden gesurft und waren nun heiß darauf die Wellen in wärmeren Wasser zu schlitzen. Aber das Wasser war platt wie das Watt. Noch nicht mal mit dem Longboard gelang es eine Welle zu nehmen. Wie so viele Generationen von Surfern vor ihnen, verleten sie ihren Surf auf die Straße. Die geschichtsträchtige Nachbarschaft Santa Monicas und Venices. Die steilen Alleen, annehmbare Skateparks und Banks – all das war verlockend. Schon bald mußten sie feststellen, dass das Skaten mit Surfen recht wenig zu tun hat. Egal wie hervorragend die Spots waren. Sicher gab es die ein oder andere Situation die dem Surfen nahe kam aber es fehlte ihnen die Wendigkeit der Surfboards. Also lockerten sie die King Pins an ihren Skateboardachsen. Das Ergebnis waren Speedwobble bei schnelleren Abfahrten, die mit losgelösten King Pins unfahrbar wurden.

Sie wußten nun welche Art von Trucks sie brauchen würden, hatten aber keine Ahnung woher sie diese bekommen könnten. Sie experimentierten mit allen auf dem Markt verfügbaren Achsen um festzustellen, dass keine der bisdato produzierten, ihren Anforderungen gerecht werden konnte. So kam es wie es kommen mußte und der erste SURFSKATE Truck wurde in der Garage hinter Neils Haus geschweisst. Um diesen zu bauen, war ihnen klar, dass sie einen flexiblen Hanger benötigten, der eine seitliche Drehung ermöglichte. Bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt war es ein reines Hobby. Greg resümiert über diese Zeit:

„Wir wollten auf den Straßen surfen. Und hätte es in irgendeinem Shop ein Achse zu kaufen gegeben, dann hätte wir sie gekauft und würden wahrscheinlich darauf immer noch die Straßen heruntercarven“

Schaute man sich zu dieser Zeit den Markt an, so bewarb ein Teil der Industrie das surfähnliche Skaten. Aber all das war nur Marketing: Bunte Grafiken auf den Boards und die gleichen Trucks die schon in den 60er Jahren genutzt wurden.

Kaum waren die Schweißnähte ausgekühlt, bestückten sie den Schwungarm mit Axiallagern, die Greg in seinem Studio hatte. Aber schon die geringste Neigung machte diese Achse unfahrbar. Sobald man sich in die Kurve legte, fuhr das Brett in die entgegengesetzte Richtung. Es stellte sich heraus, dass der Winkel der Lager invertiert werden mußte. Neil fing also an, eine neue Achse zu schweissen. Und zwar eine, die die Axiallager in die richtige Richtung bringen würde. Zurück auf der Straße fühlten sie den vermissten Snap beim Fahren. Wie kleine Kinder skateten sie den darauffolgenden Monat Tag für Tag die Hügel hinunter. Einige Sessions endeten recht abrupt, wenn mal wieder ein Teil brach, verbog oder sich löste. Sie verbrauchten Unmengen an Material während der Testphasen.

Als sie begannen steilere Hügel hinunterzufahren, kamen sie schnell an das Limit ihrer Prototypen. Um den Hanger wieder in die 0-Position zu bringen, befestigte Greg eine Art Bungeeseil an der Achse und verband diese mit der Boardunterseite. Dies war natürlich nur eine temporäre Lösung, die zwar die Skatezeit verlängerte, allerdings auch nur solange Gültigkeit haben sollte, bis Neil ein System mit Sprungfedern ausgearbeitet hatte.

Während also der Hanger nun korrekt in die Ausgangsposition zurückschnellte, fiel ihnen auf, dass er dies in einem bestimmten Winkel der fix war. So war der nächste Schritt klar: Es mußte ein weiterer Lenkwinkel her. Und dieser wurde nach mehreren Monaten der Planung gebaut, indem sie einen Double Pivot Universal Joint hinzufügten.

Nachdem die beiden alles integriert hatten, was für eine gute Performance nötig war, verbauten sie dies ine einen kompakten Mechanismus.

“Als ich an diesen Nachmittag den Prototypen testete, fühlte ich das erste Mal, dass es mehr ist als nur ein Experiment für meinen Kumpel und mich. Ich fuhr nicht zu einem Hügel um das Brett zu testen. Vor unserer Werksatt war eine Straße die eine leichte Neigung hatte. Auf diesem glatten Asphalt carvte ich einige Meter, pumpte den Weg dann zurück und das reichte mir für eine Einschätzung. All die Probleme der Vergangenhei waren weggewischt. Der Lenkwinkel gab mir das Gefühl auf dem Wasser zu sein und ich fuhr bis spät in die Nacht auf der Straße vor unserem Haus.”

Während dieser Truck in vielen Sessions getestet wurde, gab es einen Haufen Arbeit der noch gemacht werden mußte. Denn nur mit dem Prototypen war es nicht getan. Mit der Zeit wurden immer mehr Surfer und Skater auf diese Achse aufmerksam und wollten die „Carving Trucks“ haben. Der nächste Schritt war zwangsläufig die Überlegung in Serie zu gehen und einen Cast Truck zu entwerfen.

Around then Neil was working with a third-generation run aluminum foundry. The late patriarch who built the business had even cast trucks for another Los Angeles skateboard company, R.A.C.O, during the early ’70s. With a manufacturing partner in place Neil and Greg formed a company called Carver.

There was still a lot of engineering to be done before the truck was ready for production though. Taking time off from work, Neil began drawing swing arm trucks, searching for a mechanism that combined the dual-axis concept with a small but powerful and adjustable internal spring.

While the carve was truly magic, the compact spring idea still needed work, so they ended up strapping another bungee to the bottom of the board. Everyone that saw that prototype just shook their heads condescendingly. “I have to admit, it was hard to show it around at that early stage,” Neil said, “but the bungee worked well enough to get us back out on the hills testing the fine points of the geometry. It didn’t feel like some precarious prototype anymore. Greg and I were wearing down wheels to their cores every week, taking on the steepest hills we could find.”

Months were spent researching all kinds of spring systems in search of something that could fit into the cramped little space under the arm and still hold up to the heavy-duty requirements of skateboarding. Plus it needed it to be adjustable for different rider weights and preferences. It also had to increase in resistance towards the extremities, so it could act as a progressive stop. And if that wasn’t enough, it had to smoothly swing past a non-indexing centering bias, as most centering spring systems, like a swinging door spring, have an indexed ‘click’ at the center point. It turned out that what they needed didn’t exist yet.

Weeks turned into months as Neil tried to incorporate all of the disparate design demands into something that was simple, sturdy and easily made. After hundreds of drawings and dozens of prototypes, and near the end of his strained credibility, he finally cracked the solution. “I felt confident with the link-and-compression-spring design we were riding at that point. Greg and I could finally go out for a skate and not bring a bag of tools with us anymore.”

The whole process was taking much longer than anyone had anticipated, but with many solid solutions and so much already invested, they let the process dictate the pace, accepting no compromises. That next year was all about the design of the cast parts, how they could be best made and assembled, while being lightweight and strong.

The First C1 Production Parts

Compared to the uncertainty of designing the dual-axis pivots and the compact spring system, this part of the process turned out to be really fun. Translating the welded prototypes into masters for casting while knowing everything worked perfectly let the focus remain on making each casting beautiful. Once a set of drawings factoring assembly clearances and casting draft angles was complete, sculpting the final masters began. These parts are made around 3% larger than the final production parts in order to account for the small amount of shrinkage that occurs as molten aluminum cools. The masters are made from whatever works, in this case a combination of polystyrene plastic, wood and Bondo. The new truck was dubbed the C1.

Once the design was complete they began the lengthy and expensive process of securing a patent for their innovative design. It took several years to complete the process, but ultimately they were awarded their first patent.

Once the tooling and jigs were ready, they began making these new Carver trucks in small batches of several hundred and getting them into the hands of surfers and skaters.

The feedback was great. Laird Hamilton got a hold of a board and immediately connected with the way it surfed. It was his perfect surf trainer to stay in shape for riding the giants of Peahi, also known as Jaws. An innovator himself, from tow-in technology to his revolutionary Foil Board, he recognized this breakthrough in skating and saw how it dovetailed with his own cutting edge pursuits.

Caver stellte voller Stolz diverse Laird Signaturmodelle vor. Shapes und Grafiken wurden hierbei mit Laird entwickelt. Mit einem solch prominenten Botschafter etablierte sich die junge Firma in der Coreszene , denn dort gehörte sie auch aufgrund ihrer Historie hin.

Japanese pro surfer-turned-distributor Aki Takahama also felt the deep relationship to surfing he got when riding Carver Skateboards, so he took some of the boards to Japan to see if anyone there would feel the same way. No one expected the intense response they got from the local shredders. Renowned Japanese pro-surfer Mineto Ushikoshi joined the Carver team, helping to design his own line of decks and graphics in conjunction with his U4 signature brand, and added his technical surfing approach to riding the new trucks.

Die Bestellungen kamen schneller als sie produziert werden konnten. Greg und Neil machten so ihren Crashkurs in Sachen Beschaffung und Produktion.Es dauerte nicht lange und neue Produktionsanlagen sorgten für eine schnellere Herstellung und Lieferungen nach Übersee. Speziell die japanische Szene wuchs und die Fahrer überraschten mit völlig neuen Moves und ihrer ganz eigenen Art des Surfskatens.

The C7 Generation

As the market in the US began to take notice, Carver Skateboards heard different feedback than what they were hearing from Japan. American riders wanted something more stable, easier to push, more adjustable. Back in the shop Neil welded up a new prototype with a longer spring, stiffer rotation geometry and a more compact thrust bearing. It was a bit firmer rail-to-rail, which made it easier to push distances and carve steep hills. The guys preferred this version as well, so they once again made new masters and went into production. This became the C7, one of numerous new truck models slated to expand the upcoming Carver line.

The C2 Carver Skateboards

With this performance boost for the front truck, the old C2 back truck was feeling a little sluggish. So they took this ordinary workhorse and put it through the same iterative design process they applied to their other trucks. Among the improvements, they engineered it to turn a little tighter and snap back to center more positively. They also made a lower version, the C4, for street skating, with a reinforced slider plate and extra material on the hanger for longer grind wear.

With the newly completed truck line there was finally a little time to just skate and surf and think. Carver had created a fluid and reliable set of street surfing trucks, but there were other areas of the surfskate market that needed to be addressed. While there were plenty of riders who connected with the fluid feel and adjustable spring system of the C7, there were others who just wanted a more familiar truck that still gave them a surfy feel. Basically, a truck with the same two castings, bushings and pivot pin of a standard truck, but reconfigured into a new geometry that loosened up the nose of the board and performed like a cross between the C7 and a standard truck.

“I started calling it the CX because it was still a mystery to me, and instead of giving it a model number, I just wrote ‘X’,” said Neil about this new truck. He worked on in it spurts for years, trading between helping to build the Carver brand and diving into research and development.

Around this time, a large distributor approached Carver interested in taking their boards to a broader national market, and asked if they had a simpler model of carving truck. It was the perfect situation for the CX, so the guys brought their latest prototype to the meeting, pitched them on the idea and the distributor loved it. Only it didn’t really work yet! All of a sudden the future growth of the business hung on solving that mystery. “I went through the previous years of research, skating old prototypes and making new ones, all in search of that magic feeling. I made graphs of the various elements of truck geometry and set about systematically charting the effects of various subtle changes on turning performance”.

It became all about understanding what each angle and proportion felt like underfoot. “For each new prototype I only changed one thing at a time so its effect could be isolated and measured,” Neil explained. With an understanding of these effects, he combined the elements he knew would produce the specific performance they wanted. To the casual observer, all the prototypes of that period look the same. Indeed, some of the changes were only a few degrees of kingpin angle, for example, but the effect on performance was dramatic. After almost five years of making prototypes that didn’t work, it seemed as though this whole idea might be a futile pursuit. But just as it seemed like it was never going to work, a few of the right tweaks resulted in the first RKP truck that carved and pumped, where all the other prototypes just turned.

It became all about understanding what each angle and proportion felt like underfoot. “For each new prototype I only changed one thing at a time so its effect could be isolated and measured,” Neil explained. With an understanding of these effects, he combined the elements he knew would produce the specific performance they wanted. To the casual observer, all the prototypes of that period look the same. Indeed, some of the changes were only a few degrees of kingpin angle, for example, but the effect on performance was dramatic. After almost five years of making prototypes that didn’t work, it seemed as though this whole idea might be a futile pursuit. But just as it seemed like it was never going to work, a few of the right tweaks resulted in the first RKP truck that carved and pumped, where all the other prototypes just turned.

So unique was this geometry that the USPTO granted Carver another truck patent for it. In the end, that large distributor ripped them off, nearly bankrupting the small company. It was the first of many business lessons to come, and a model for how to overcome those problems. Even in spite of all that, it still felt like they had come out ahead. They now had another important part of the line, the new CX.

The Pipewrench

Meanwhile, Greg had been pursuing the design of a skate tool that was as functional and well designed as the other products in the line. It was nice to be able to adjust your ride on the fly with a compact pocket tool, and all the other available tools were too big and often poorly made. By now Carver had firmly established a protocol for product development; keep making prototypes until everything works perfectly, and only then move on to production. The consequence of this philosophy is that it takes an almost unreasonable amount of time to finish a new design. Few companies can afford such a protracted research and development program, but Carver wasn’t interested in just putting out another product. They were designing these things for themselves, and they needed to be completely satisfied with them. The formula is simple: more work you put into design, the less work it will take to use it.

Two years later they rolled out the Carver Pipewrench, a compact stainless steel skate wrench with a magnetic Allen key catch that performs every adjustment a skater could need. You can completely rebuild any truck in the line, including the C7, with this little nugget.

With so much effort put into product design on the one hand, and manufacturing processes on the other, early marketing remained mostly word of mouth. Which was not so bad.

“We witnessed countless companies rush into the marketplace with hastily thought out products and big ad campaigns and then simply disappear the following year” Neil said. “We decided to build a long term, grassroots base and service it the best we could, and let our growth occur organically.”

The Gullwing Charger

Around this time Sector 9 was looking for a new truck to launch their reboot of the classic Gullwing truck company. President Steve Lake had been looking at every truck on the market but couldn’t find one he liked, so he made an offer to Neil; make him a truck he likes in 4 weeks and they would produce the design and pay him a royalty for each truck sold. It was just the kind of challenge Neil was looking for; he had accumulated a lot of esoteric truck knowledge over the years and liked the idea of making a mainstream truck with Gullwing’s mass distribution. Neil had ridden Gullwing trucks as a kid too, so the project had an added resonance.

Over the next year Neil would go on to make and name an entire line of trucks for the historic brand, from the Charger, the main truck in the line, to the Bomber (a downhill truck), the Grinder (a street skating truck) and the Transaxle (an innovative RKP street truck that was never mass produced).

A New Carver

By 2007 recognition of the brand was growing, but the company was having some internal problems they just couldn’t seem to shake. For one, whenever the factory produced a big order, they always ran short on some very small part that held up the entire shipment. Vendors were calling for late payments and it was hurting their relationships. All this was impacting the bottom line and they seemed to be always out of money, even though sales were good.

At that time the business was divided between manufacturing and shipping, which was run from the foundry in the City of Industry, and the design department that Neil and Greg ran from Venice. The design department was fully focused on developing new product, as well as producing videos that showcased Carver surfskating on the local hills.

As the separation between the two halves of the company increased, Greg and Neil felt at odds with how fulfillment was managed. They went to the factory to set up systems, but without constant supervision the issues always crept back soon enough.

The rift between the Eastside factory and Westside designers eventually came down to a standoff. Eastside wanted to keep operations at the current factory, Westside wanted to move everything closer to the beach where they could keep a closer watch on fulfillment. Neither side was willing to compromise. Eastside didn’t think a couple of surfer-artists could fund or run a factory, Westside didn’t believe the problematic factory culture could ever change. The company was a crossroads. After lengthy negotiations, in late 2007 Neil and Greg borrowed against their homes and bought back all the outstanding shares in the company and set up a small factory in the beachside city of El Segundo.

It was an enlightening transition. In 2008 the Great Recession hit hard and fast, and the guys had to negotiate new terms with vendors they owed past balances to, as well as run the office, help make boards, pack, ship and still keep up with promotion and product development. They didn’t have a lot of cash reserve, and if it ran out, they’d sink and lose their homes, so they made sure they did everything right. First they had to convince all their vendors and customers that this was a new Carver, one that paid its bills and delivered on time. And now that the guys were in charge of every aspect of the company, it was finally a promise they could keep. The business slowly regained its footing and rebuilt all it’s relationships.

During this challenging time the Gullwing Charger was selling on thousands of boards every month, and the project was paying royalty dividends that further helped to support the growing brand.

A New Era For Surfskate

Carver Skateboards fully recognized that it was a bastard child to the skateboarding world with its soft wheels and surfy deck shapes. Skateboaring culture had evolved away from its surfing heritage and had evolved into a tight knit culture closed to anything but the prevailing ‘street style’ of riding. So Carver Skateboards embraced this difference and decided to take it’s meager ad budget and focus on the one publication that reached the core of their riders: Surfer Magazine.

The guys were now faced with how to communicate the innovative performance of their boards when countless other skateboard companies had already promised a ‘surfing experience’ and failed to deliver on anything more than a longer deck with a picture of a wave on it. Videos were able to show the unique boards in action, but with a single still photo it just looked like you were surf-styling on a regular cruiser. Working with new team rider Taylor Knox and legendary surf photographer Art Brewer, they set out to show the impossibly tight cutbacks on a single page using numerous composited figures that showed the whole maneuver as a sequence. It was like playing a short video clip on the page.

This style proved to be the winning ticket. Surfers were able to truly see what kind of riding was possible, and along with the an increased presence in surf shops nationwide, surfers were able to try out demos of the boards and feel the performance for themselves.

State of Surfskate 2014 from Carver Skateboards

It’s been nearly 18 years since that flat summer, and Carver Skateboards is going strong and still growing. The new factory is humming along, the latest product line covers a comprehensive range of riding styles, video production is showcasing an exploding list of talented Carver riders, and the company has a solid base of distribution worldwide.

Josh Kerr has recently joined the team with a pair of new pro models, and future collaborations are in development.

As skateboarding evolves to be more inclusive of innovation, historic styles such as Surfskate are finally re-emerging on the scene. There are numerous other surfskate brands now, mostly in Japan and Australia, where nearly a dozen brands try to make trucks modeled after our signature dual-axis invention, with mixed success. As the leader in this charge, Carver Skateboards continues to make the most trusted and reliable American-made surfskate equipment available, develop cutting edge innovations, and drive progression forward for all the dedicated riders who rely on our equipment for surf training and just a fun way to surf the streets.

“I see people on our boards all the time now, and I can always tell when they’re riding a Carver by the way they’re surfing their boards,” Neil says. “It’s such a great feeling to watch how much fun they’re having, and knowing we made that for them” adds Greg.

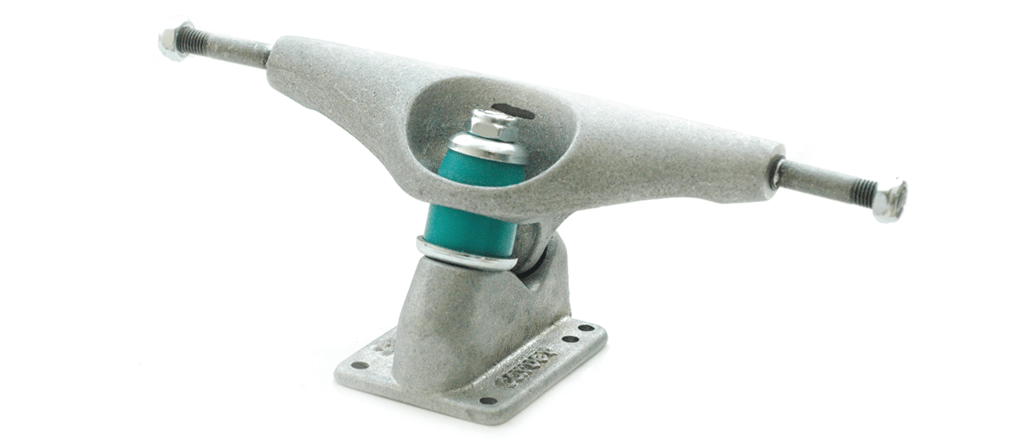

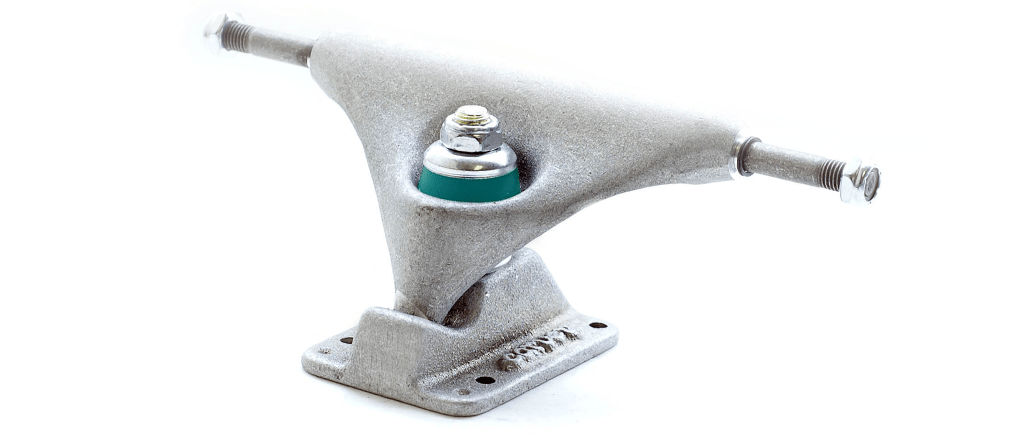

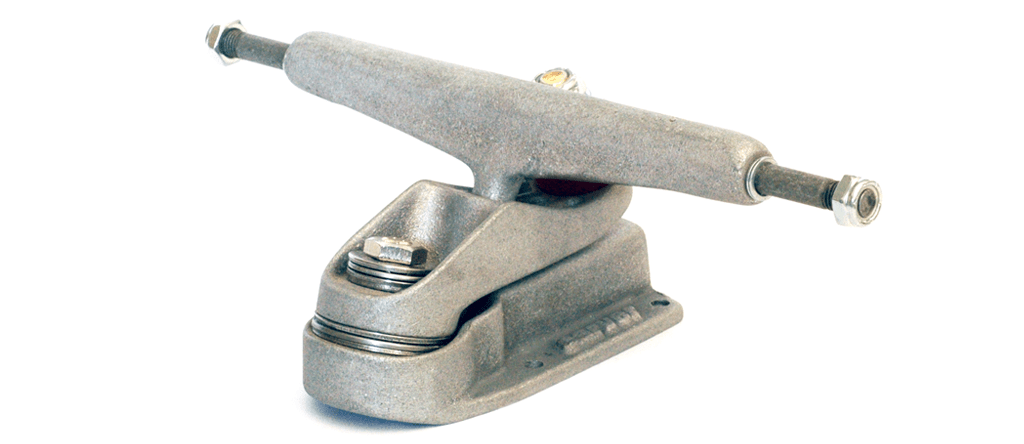

Achsensysteme

from Carver Skateboards

from Carver Skateboards

from Carver Skateboards

from Carver Skateboards

Kontakt zu

Carver Skateboards

Tel: (310)648-8249

Fax: (310)648-8251

Email: mail@carverskateboards.com

Carver Skateboards

Carver Skateboards

Carver Skateboards